The Tree of Life: Recovering a Medieval Sacred Drama

Mara Nerbano (2019)

The title of the play in fact alludes to three “Trees of Life.”

All are associated in some fashion with the historic parish church of San Giovenale, founded in 1004.

An influential devotional work entitled Lignum Vitae (The Tree of Life) was written in the 1260’s by the great Franciscan theologian Saint Bonaventure, locally born in nearby Bagnoregio. A 14th-century fresco in the rear of the church explicitly illustrates Bonaventure’s Tree of Life. A medieval play from Orvieto featuring the Tree of Life was very likely performed in San Giovenale.

Dr. Mara Nerbano, the chief contemporary historian of the rich tradition of religious drama developed in central Italy during the medieval period, presented a public lecture that provided an historical framework for performances of L’Albero della Vita in February 2017.

Professor Nerbano addressed three themes in particular: the origins and scope of the texts used in the play; the identification of the church of San Giovenale as a place of theatrical performances; and an interpretive hypothesis about the use in the medieval period of the laude – a particular genre of sacred theater, or sacre rappresentazioni.

Her hope, said Dr. Nerbano, was “to offer some helpful perspectives on recuperating this repertory in contemporary theater.” The essay that follows is the text of her talk, translated from the Italian by John Skillen.

1. Le laude, i disciplinati, le confraternite

The principal sources of the recent production are found in the Laudario Orvietano, a collection of sacre rappresentazioni compiled in 1405 by a certain Tramo di Lonardo. The manuscript (catalogued in the National Library of Rome as manuscript Vitt.Em.528) contains 37 plays.

The plays preserved in the Laudario Orvietano are ordered chiefly according to the holy-days and saints days punctuating the church year. Such an arrangement is not surprising since the dramas performed throughout medieval Europe were typically linked with the liturgical calendar. Visible damage to the 64-page manuscript makes it clear that the original collection contained more than the existing 37 plays. For instance, a set of missing pages, given their place in the overall order, would almost certainly have contained plays dramatizing events of Holy Week.

The term Laudario typically indicated a collection of so-called Laude: poems often sung, and written in the vernacular, that is, not in Latin but in the local dialects used by ordinary folk.

For many Italians, the term laude will call to mind the dramatic poems composed by the Franciscan poet Jacopone da Todi (1236-1306). Written in the language of his own time and region, the laudario of this Umbrian poet from the hilltop town of Todi (guarding the valley to the east of Orvieto) is often described as a “personal laudario” in order to underline the remarkable originality and uniqueness of his compositions, the exact purposes of which remain the subject of intense historical debate among the scholarly community.

The authorship of most of the medieval laude remains anonymous; they were the fruit mainly of the confraternities, or associations of laity established for the purpose of coming together for common prayer and shared acts of devotion. Such social-religious sodalities were inspired, in part, by a desire to participate more fully in the mysteries of faith formally enacted in the liturgy, the Latin of which was becoming ever less comprehensible to the simple faithful.

The devotional practices of these confraternities of laudesi typically took one of two directions. Some were focused on the Virgin Mary, and developed a repertory of prayers of praise – lyrical laude – dedicated principally to Mary and the saints. Others of these devotional associations took on a deep identification with Christ’s suffering in his Passion. The characteristic practice of such confraternities of disciplinati was that of corporate flagellation, often with iron scourges.

An important innovation of the disciplinati was that of introducing laude in dramatic form, in which various personages performed in dialogue and formalized action episodes taken from the Gospels, from hagiographic texts and from spiritual literature. When many of the manuscripts of these laudewere brought to light in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, scholars identified them as the origins of Italian theater, identifying them as the first examples in the entire Italian peninsula of dramatic literature in the vernacular.

The oldest and most significant collections of these laudari are found in Umbria, and can be traced back to three centers of production: Assisi, Perugia, and Orvieto. By 1325 in Assisi, plays were being composed in metrical forms typical of the laude of the disciplinati, reworked in great part from a preexisting repertory of laments of the Virgin intended for the celebrations of Holy Week. In Perugia, between 1325 and 1340, the scope of the productions grew to encompass the entire cycle of the church year, with dramatized laude created for all the major feast-days and saints days of the liturgical calendar. By the beginning of the 15th century in Orvieto, additional innovations at the metric, musical, and thematic levels were being developed.

Orvieto, Archivio Storico Comunale, Ospedale S. Maria della Stella, ms 827

Such innovations are exhibited in the Laudario Orvietano, compiled in 1405 by Tramo di Lonardo. In a statement at the beginning of the manuscript, Tramo identifies himself as a member of the confraternity of disciplinati of San Francesco in Orvieto, and his intention as bringing together the repertory of the various confraternities of the city:

«Queste sonno le ripresentatione le quale si degono fare l'anno per le fraternite d'orvieto e scripte nel presente libro per me Tramo di Lonardo disciplinato de la fraternita di santo francesco benedecto nele Mille CCCCV e del me d'aprile»

[These are the representations worthily performed by the confraternities of Orvieto and written in the present book by me, Tramo di Lonardo, disciplinato of the fraternity of blessed Saint Francis in one thousand four hundred five in April.]

(More details about the contents of the volume are given in a Note at the end of this essay.)

In the archives held in the old Hospital of Santa Maria della Stella in Orvieto I was able to find two other codices that documented the later history of the sodality. The first of these is a sort of inventory of items from the ospedale of the disciplinati of San Francesco from the years 1480-1573. The second contains the statutes of the confraternity from 1573, of particular value not only because it deals with the only statute of a company of Orvietano disciplinati that has come down to us, but also because it attests how, still in this later period, the confraternity brothers continued to dedicate themselves to the rites of the disciplina and to singing of the laude.

2. La chiesa di S. Giovenale come luogo teatrale

Photograph courtesy of Mark Shan

The decision to set a new production of L’Albero della Vita in the church of San Giovenale was motivated not so much by the suggestiveness of this jewel of romanesque-gothic architecture itself as by the references to the church in the Laudario Orvietano. The first play in the anthology – a dramatization of the Creation and Fall, and a rare example of a lauda that draws its sources from the Old Testament – is introduced by a rubric that explicitly associates the play with the church: «Questa ripresentatione si fa como dio patre fece il mondo el cielo e la terra e fassi per quelli di santo Iovenale» [This representation depicts how God the father made the world, the heaven, and the earth and was made by those of saint Giovenale].

This note is the first documented reference to a confraternity dedicated to Saint Juvenal (Giovenale in Italian, an early evangelist of Umbria). The obvious supposition would be that the confraternity was tied to the church of the same name, yet this is not a necessary conclusion. In Orvieto itself, for instance, a confraternity dedicated to Saint Martin had its seat not in the church named after Martin, the saintly bishop of Tours but rather in the cathedral. Nevertheless, the presence of a company of disciplinati based in the church of San Giovenale is confirmed in a document of fifty years later, where the Orvietano notary ser Matteo di Cataluccio, in his chronicle compiled from 1422 to 1458, registers the notice of the burial in June of 1453 of his 22-year-old nephew (or grandson) “in the church of San Giovenale in a tomb of the disciplinati” (Mortuus est Catalutius Cole meus nepos carnalis iuvenis XXIJ annorum vel circa, et fuit sepultus in Ecclesia Sancti Juvenalis in pilo Disciplinatorum).

Photograph courtesy of Gregory Schreck

Other hypotheses credibly follow. It makes sense to assign to the repertory of this same confraternity the concluding text of the manuscript, a hagiographic play that dramatizes the election of San Giovenale/Saint Juvenal as bishop of Narni: «Questa ripresentazione si fa come sancto Iovenale fu facto vescovo di Nargne».

This composition contains an additional point of interest. In the concluding verses of the play, the protagonist announces that he will now go to say Mass in the place assigned for prayer (ll. 189-192: “Ie vo a diciar la messa/ nel luocu diputato per oraculi/ e con divotione ad essa/ starete vo’ ne’ vostri tabernacoli”), suggesting a sort of trespassing or crossing over from the para-liturgy of the confraternity into the official liturgy. (In a 1935 study of the stage sets of sacred drama, Virginia Galante Garrone took these lines to indicate that the representation must have been staged in a church and that the part of the protagonist was played by a priest.)

Photograph courtesy of Mara Nerbano

Taken together, these pieces of evidence support the likelihood that the same confraternity was responsible for a third lauda (number 27 in the Laudario Orvietano collection) that stages a discourse of Christ with his disciples and the three virtues of Faith, Hope and Charity imagined around a great Tree of Faith on Mount Tabor: «Questa representatione si fa: come Cristo apparve a l’apostoli nel monte e a la Fede e a la Carità e a la Speranza e volse udire da loro in che modo avieno predicato per lo mundo ad confermare tucta la Fede del suo arbore»

Although imagery of symbolic trees was widespread in the Middle Ages, the motif is rather unusual in religious theater. Hence it is tantalizing to consider the possible connection of the play with a fresco on the inside of the entrance of the church of San Giovenale depicting another symbolic tree: the Lignum Vitae, the Tree of Life.

3. L’Albero della Vita: laude, iconografia e prospettive interpretative

This particular lauda of the Tree of Faith was chosen as the principal text for the recent new adaptation of L’Albero della Vita prepared by Andrea Brugnera and John Skillen and their team of actors and musicians. Grafted onto this main trunk are passages from other texts rich with arboreal symbolism. Inserted into the opening part is a fragment from the first play in the collection (“Rappresentazione della Creazione”) narrating the Creation and depicting the temptation of Eve. The reason for this choice is twofold, since, beyond evoking the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil, the composition was presumably performed in the same space and as a work of the same confraternity. To this was added another passage treating the same episode, taken from the Jeu d’Adam, an Anglo-Normal text from the 12th century that constitutes the earliest drama in the vernacular documented in Europe. It is the only passage in our adaptation not of Umbrian origin. We also inserted a lauda from Perugia, “O arbor fino, co’ se’ te abondente” (O tree refined, so abundant) from an anthology from the first half of the 15th century, the Laudario Vallicelliano. “O arbor fina” was included among the compositions used by the disciplinati in their prayers on Sunday (“pro dominicis diebus”). It is a song recited in praise of the Cross imagined as a tree adorned with gems, pearls, precious stones and delicate flowers that blossomed from the blood of Christ. In the concluding section of the play we inserted a passage from a lauda composed by Jacopone da Todi, “Omo che può la sua lengua domare,” that develops the theme of the Tree of the Virtues and presents interesting analogies to the contents of the Orvietan rappresentazione.

One of the problems posed by this repertory of enacted laude is to understand exactly how and for what purposes they were used in the medieval period. There is no doubt that some texts were not only enacted in the private ceremonies of the confraternities, but also performed publicly. Lists of actual costumes and theatrical accessories are often included in archives of the period, and turn up sporadically in chronicles. The conventions of such dramatic performances would obviously have been quite different from those that we might expect today. The actors were amateurs, only occasionally drawn from professionals. They were sung with typical melodies, which unfortunately have not been handed down to us in the manuscripts.

Among those texts surely intended for public performance would have been the play of the Creation. The text in the Laudario Orvietano suggests a clear sense of staging, with numerous references to places and the actions and movements of the performers. For example, the episode of the Temptation of Eve probably called for a scenic element representing a tree which provided a focal point for the gestures of the actors and around which the action revolved. Perhaps they could have utilized costumes, masks, and other artifices. An account, for example, of a theatrical representation on the same subject in the Umbrian town of Foligno indicates that the confraternity of San Feliciano made use of a “serpent” equipped with wings and with a face in the likeness of a woman. In fact, the inventories of this particular confraternity include, among other objects, “a pair of wings of the falcon serpent, and a serpent of cloth, that deceived Adam” (1425); “the serpent of Adam and Eve” (1450); “a serpent with the visage of a woman” (1466), and “a snake that tempted Eve” (1478).

Photograph courtesy of Lorenzo Scoppoletti

It is my opinion, however, that the lauda was mounted with very basic staging. In several places in the text, reference is made to movements up and down, as when, having created the various hierarchies of angels, God the Father says, “discendar voglio e ’l mondo vo’ fare” [I want to descend and make the world] (line 150). When Adam and Eve are caught committing the original sin, God says: “Andatela a·ccacciare/del paradiso al mondo tempestosu,/ e cussì stien là giuso” […there below] (lines 217-219). In his influential study of the origins of Italian dramatic literature (1924), Vincent De Bartholomaeis extrapolated from these lines an imposing apparatus of staging with two levels one above the other.

And yet the nave of the church of San Giovenale rises by three steps from the lower back half to the higher apse end of the building. The ascending and descending movements could have been accomplished simply by using the architectural space as it existed. The likelier supposition is that the play was composed for presentation in this very church, effectively exploiting its own architectural features. (The deliberate interpenetration of play-space and actual space is a common feature of the sacred theater of medieval Europe.)

Photograph courtesy of Lorenzo Scoppoletti

I believe that such in situ dialogue between play and the church could have occurred with the lauda of the Tree of Life just as well. We can credibly imagine the play being performed under the eyes of the painted image of the Tree of Life. In fact, the text is notable for its lack of any real dramatic action that would require individuated movement. Instead, various independent passages are simply set side by side with one other in a paratactic structure without connecting links. First, Christ introduces the theme and points ahead to the participation of the Apostles. Then follows the passage, possibly collated out of place, in which the Theological Virtues of Faith, Hope and Love present themselves as the base, middle part, and summit of the Tree. Next, the Apostles take their turn, reciting in the vernacular the phrases of the Creed. John the Baptist intervenes with a speech illustrating the salvific value of baptism. Then follows a more fully-developed and emotionally-laden laude of lament spoken by the Virgin to her son, imploring him to pardon the sinners. The concluding word returns to Christ, declaring immediate pardon and blessing to the bystanders with the sign of the cross. The epilogue is entrusted to two Angels who chant the “Glory be to the Father.”

If one looks at the contents, the lauda seems to take up more of a catechetical purpose that opens into theatrical dimensions. Yet the text includes a number of explicit references to a tree, even if the exact referent is dependent on context. In the opening lines, Christ exhorts the angelic hierarchies to behold the Tree of Faith: “Tucta mie compagnia,/ electe gerensie di ciascun coro,/ sguardate ’l mie thesoro/ all’arbore nato de la fé mia” [..the tree born of my faith] (ll. 1-4). Several lines later, he makes the same invitation to the Christians: “Cristïam, risguardati/ all’arbor de la fé che fu ’nalzato” (ll. 16-17). Soon after, each of the figures representing the Theological Virtues refers to a tree: “La fede son chiamata,/ che di questo bell’arbor son pedone” [Faith is my name, who am the base of this tree] (ll. 37-38); “Ïe so la speranza,/ che nel mez<z>o dell’arbor agio ’l sito” [I am Hope, who has my place in the middle of the tree] (ll. 45-46); “Carità so ardente/ zelo fervente ·dd’infiammato amore,/ dell’arbor excellente/ solu la sollicita lu splendore” [I am ardent Charity, the fervent zeal that inflames love …] (ll. 53-56). Charity, moreover, appeals to the metaphor of the Tree of the Cross “Dico che nel cuor porto/ suo passïone e quel legn’amoroso” [I say that in my heart I carry his passion and that loving wood] (ll. 73-74). The image of the tree returns finally in the speech of the Virgin, who associates it with Christ himself: “Tu si’ arbor e fede/ e·ssi’ speranza a ciascun peccatore,/ però che chi ti crede/ verrà in cielo a te, dolce amore” [You are the tree of faith, the hope of every sinner, whoever believes in you will be with you in heaven, sweet love] (ll. 197-200). Although the Tree may not be the object of any dramatic action, it stands consistently as the backdrop of the discourse.

Photograph courtesy of Lorenzo Scoppoletti

But what can be said definitively about the relation between the laude and the fresco? Regarding the lauda, its principal theme is that of the Tree of Faith, with its twelve branches corresponding to the articles of the Creed. But the composition also evokes the Tree of the Virtues. Faith, Hope, and Charity are the vehicles by which humans ascend to the heavenly kingdom and take their place with the angelic hierarchies. It is the same tree described in Jacopone da Todi’s lauda, partially inserted in the play, where the motif of the tree is used to represent man perfected through the various stages of ascent to God.

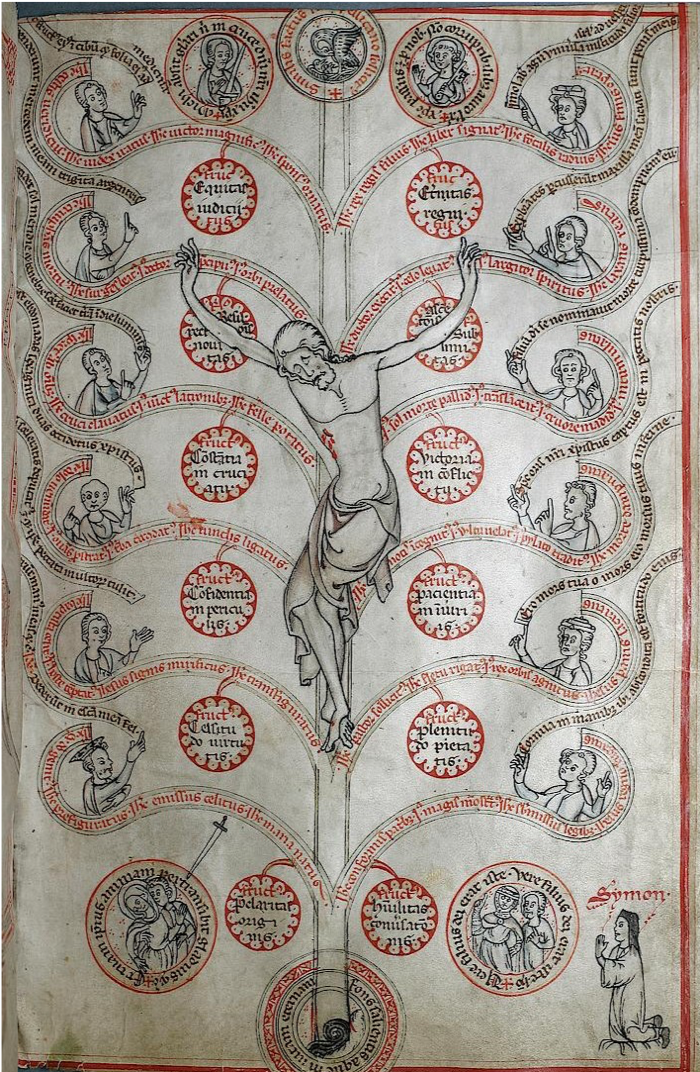

Regarding the fresco, it repeats an iconographic theme taken directly from the influential devotional treatise written by the great Franciscan theologian born only a few miles from Orvieto, namely, the Lignum Vitae (The Tree of Life) of St. Bonaventure of Bagnoregio. The purpose of this small work, composed around 1260, was to stimulate meditation on the life of Christ. As the author himself states in the prologue,

To enkindle in us this affection, to shape this understanding and to imprint this memory, … I have arranged in the form of an imaginary tree the few items I have collected from among many, and have ordered and disposed them in such a way that in the first or lower branches the Savior’s origin and life are described; in the middle, his passion; and in the top, his glorification. (pp. 120-21 in the Classics of Western Spirituality edition of selected works of Bonaventure)

While writing in deliberately simple and accessible language (“I have used simple, familiar and unsophisticated terms to avoid idle curiosity, to cultivate devotion and to foster the piety of faith”), Bonaventure synthesizes in the immediately-comprehensible scheme of the tree an extraordinary richness of biblical and theological references. The treatise invites interpretation on several levels, in a manner that could be appreciated by a cultured public, able to decipher its complex symbolism, and accessible to a broader public of lay people for whom it could guide a personal meditative journey.

Almost immediately Bonaventure’s book prompted visual images of the Tree, beginning with the manuscript tradition. Initially these images took on a schematic character, as in the miniature that accompanies the codex in the Apostolic Library of the Vatican (Vat.Lat. 1058, c. 28v), dateable to around 1290, the earliest example that we have. But such diagrams were soon enriched by figurative details, including the representation of Christ crucified, of the Prophets, and of other figures not directly dependent on the text. The earliest example of this type is found in a codex from about 1300 where, at the foot of the cross, along with the patrons, appear the Virgin on the left, swooning in grief and held up by Saint John, and to the right of the cross, the centurion who recognized Christ as the Son of God (traditionally given the name Longinus), together with another feminine figure (codex #2777 of the Hessische Landes und Hochschulbibliothek of Darmstadt, c. 43r.; top image on right). In another beautiful miniature from around 1310, now in the British Library, the Lignum Vitae is enriched by additional biblical citations. It is part of a collection of 24 images including an Albero delle Virtù (Tree of the Virtues), in which the phrases of the Creed are associated with the twelve prophets and the twelve apostles (British Library, Arundel #83, c. 125v; middle image on right; and Arundel #83, c. 128r; bottom image on right). (Such visual summaries of complex doctrinal themes, eventually referred to as Specula theologiae [mirrors of theology], often served as compact compendia of materials for preachers to use in composing their sermons – as Lina Bolzoni has studied in her The Web of Images, a groundbreaking study of the relations between words and images in medieval vernacular preaching.)

Taddeo Gaddi, Tree of LIfe, refectory of Santa Croce, Florence; photograph courtesy of John Skillen

Once the iconographic conventions were regularized in the books of miniatures, these richly illustrated schematic images of the Lignum Vitae began to circulate in other media, and finally in large scale paintings such as the fresco of the Tree of Life in the church of San Giovenale. Four other examples of Trees of Life still exist in Umbria. A miniature in the Library “Augusta” in Perugia (codice 280 [E 27], c. 100r) is given the date of 1301; a fragment of a sinopia (the underdrawing beneath the layer of plaster supporting the final fresco) is preserved along the bottom of the wall of the dining hall of the convent of San Francesco in Gubbio, dated to the third decade of the 1300s; a fresco at the bottom of the apse of the church of San Lorenzo in Borgo Cerreto in Valnerina, probably of the same time; and a fresco in the monastery of Sant’Anna in Foligno, probably from the first decades of the 15th century. Certainly the most well-known (and accessible) version of the Lignum Vitae in central Italy is the monumental fresco on the end wall of the refectory in the Franciscan monastery of Santa Croce in Florence, the work of Taddeo Gaddi in the mid 1300s. The chapter titles from Bonaventure’s treatise are still clearly legible in the scrolls along each branch of the Tree.

Photograph courtesy of Mara Nerbano

The fresco of the Tree of Life in San Giovenale exhibits similarities with the illustration of the codex in Perugia, placing it in the miniature tradition and likely datable to the first decade of the 14th century. At the center of the composition is Christ Crucified. Branching off the Cross are twelve scroll-like strips with twelve fruits. Although the phrases in these scrolls are severely scuffed and damaged, close inspection readily confirms that they are direct citations of the phrases that begin each chapter in Bonaventure’s devotional treatise.

Photograph courtesy of Mark Shan

Notably, however, the image is enriched by numerous details not found in Bonaventure. Wrapped around the top of the cross, for example, is a serpent that recalls the connection with the Tree of the knowledge of Good and Evil. To the right, on the part of the fresco that continues on the adjacent column, is represented one of the thieves. Among a group of figures gathered at the foot of the cross we can identify, on the left side, the fainting Virgin supported by the pious women, Saint John the Baptist, Saint Simeon, and, on the opposite side, a figure perhaps representing the Synagogue and the centurion who pierced Jesus’s side with his lance. At the base of the tree, in seated position, is a rare representation of Christ Emmanuel, who holds up two scroll-like banners with two phrases from the hymn In honore sanctae crucis composed by Venantius Fortunatus in the late 6th century. Kneeling at the very bottom of the cross, arms raised, his back to the viewer, is a figure in Franciscan habit, credibly identifiable as Saint Bonaventure. The scene is framed by a series of tondi with busts of prophets and apostles who hold up scrolls with scriptural texts, now difficult to decipher. Outside the frame on the lower right is depicted the female donor, kneeling and presented by Saint Juvenal in his bishop’s vestments.

The contents of the fresco clearly do not correspond to the text of the lauda. Yet this fact does not invalidate the possibility, even the likelihood, of a closely-experienced relation between painting and play, nor even the hypothesis that the lauda could have been in some manner generated by the painting. The collections of Specula theologiae provide examples of diagrams of virtues and schematic designs of the Tree of Life within a few pages of one another, allowing such mutual influence. In her close study of one such text, a Colloquio spirituale, Lina Bolzoni has underlined how the same codex was the base of both texts and images, and of the translation of texts into images and images into texts: “Not only is the text translatable into image, but the image can in its turn generate new segments of text. The process is one of mirroring, but also of diffraction and multiplication” (The Web of Images, 57).

What we can say on the basis of medieval relations between text and image is that the performance of the lauda in close association with the fresco would have activated relationships – sounded resonances – of considerable complexity (which this brief essay cannot elaborate). It is enough to say that the combination of diverse elements and expressive instruments, spoken words, words taken from books, words expressed by figures in the fresco, must have anticipated diverse levels of reading. They would have accommodated various manners of reception whether the public was literate or illiterate, capable of holding in mind multiple intertextual references at once, or needing to follow a step by step sequence of comprehension. The intent, in any case, was always that of acting on the interior, of strengthening awareness, and of elevating the understanding of the faithful. To cite Bolzoni a final time: “The literary text, the image, the mixed product of painting and writing, all have the task of building mental images capable of operating on the faculties, of setting into motion an ulterior process of knowledge, meditation and spiritual elevation” (The Web of Images, 56), or in Saint Bonaventure's phrase, "To enkindle in us this affection, to shape this understanding and to imprint this memory."

The cliff of Orvieto at sunset on a blustery day, with the church of San Giovenale standing as sentinale of the town. (Photo credit Peter Whitten)

Translator’s note:

Mara Nerbano is the chief contemporary historian of the rich tradition of religious drama developed in central Italy during the medieval period, author of Il Teatro della Devozione: confraternite e spettacolo nell’Umbria medievale as well as a number of academic articles. Her book The Theater of Devotion (not yet translated into English) serves as an important scholarly source for the collaborative work of three associations (Studio for Art, Faith & History, Compagnia de’ Colombari, and KaminaTeatro) to revivify – and add to – Orvieto’s own tradition of such sacred dramas. Dr. Nerbano is a native of the small town of Allerona, located just off the cliff from Orvieto. She accepted an invitation from Andrea Brugnera and John Skillen (director and producer of several recent dramas performed in Orvieto) to serve as the academic advisor to the production of L’Albero della Vita, or The Tree of Life.

Note

The volume in which Tramo di Lonardo’s collection of plays is found includes other documents as well which are useful in reconstructing the history of the confraternity that produced some of the plays. These have particular value since all the archival sources of the Orvietan confraternities have disappeared. Along with an inventory and a register from the beginning of the 14th century from the little-known confraternity of Saint Maria, the codex contains a register of the confraternity of San Francesco from the years 1337-1480 and a list of deceased members from the years 1324-1398. An examination of the names of the members of the sodality indicates that it was founded on October 1st, 1323 by the friar Ianni de Pustierla and that several prominent personages from Orvieto were also members. Among these, Ermanno Monaldeschi, lord of Orvieto from 1334 to 1337, was registered along with at least two of his sons, Mannuccio and Monaldo. Various members came from the Ranieri family, including Neri di Zaccaria, who had been “capitano del popolo” in 1316-1317, with his son Cesare and, perhaps, his nephew Domenico di ser Ciuccio, who was probably the son of his brother Benedetto (detto Ciuccio) di Zaccaria. The ancient nobility was represented by a Francesco di ser Farolfo, mentioned in 1381, very probably of the clan of Montemarte. The principal group of members, however, would have come from the various guilds of the artisans (the Corporazione delle Arti), surely including representatives from the locksmiths, knife-makers, tailors, potters, and one member identified as the son of a goldsmith. Also involved would have been members of the clergy, both those holding parish and diocesan offices and those belonging to the monastic communities (the so-called “secular” and “regular” clergy). Tramo di Lonardo himself, who dated his own entrance into the confraternity as April 13th, 1396, was a canon of the Duomo as well as a licensed notary, as indicated by the title deeds preserved in the Archives of Orvieto for the years 1404-1447.

Sources and References

Laudario Orvietano, a cura di Gina Scentoni, Spoleto, Centro Italiano di Studi Sull’Alto Medioevo, 1994.

Roma, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, ms. Vitt.Em. 528.

Orvieto, Archivio di Stato, ASO, Archivi Vari, Ospedale S. Maria della Stella, Istrumentario a. 1480-1583, ms. 827.

Orvieto, Archivio di Stato, ASO, Archivi Vari, Ospedale S. Maria della Stella, Capitoli della confraternita di S. Francesco a. 1573, ms. 829.

V. De Bartholomaeis, Origini della poesia drammatica italiana, Bologna, Zanichelli, 1924.

V. Galante Garrone, L’apparato scenico del dramma sacro in Italia, Torino, Rosenberg e Sellier, 1935.

M. Nerbano, Il teatro della devozione. Confraternite e spettacolo nell’Umbria medievale, Perugia, Morlacchi, 2006.

L. Bolzoni, La rete delle immagini. Predicazione in volgare dalle origini a Bernardino da Siena, Torino, Einaudi, 2002 (English translation as The Web of Images: Vernacular Preaching from its Origins to St Bernardino da Siena, Burlington VT, Ashgate, 2004).

A. Simbeni, L’iconografia del Lignum vitae in umbria nel XIV secolo e un’ipotesi su un perduto prototipo di Giotto ad Assisi, in “Franciscana. Bollettino della Società Internazionale di Studi Francescani”, 9 (2007), pp. 149-183.